by Manny Santiago

Guilty pleasures. Everybody has at least one. Ask around. Your family and friends aren't likely to spill it that quickly. It takes quite a few cocktails and not a little bit of tact to get it out of people you know well. Which stands to reason, after all, you know them. They have to face you again, likely soon, and knowing that you know what makes them tick is a bit, well, unnerving.

Strangers, on the other hand, that's another story. People you don't know, who don't know you, are more likely to tell you the truth, and quickly. Would it surprise you to know that, under the guise of Psych 101 experiments back at university, I used to ask all the volunteers what their guilty pleasure was and, quicker than Musashi in a sword fight, people were willing, no they wanted - got excited in fact - to tell their secrets to someone, especially their dark ones. I recorded quite a lot of the following:

Deep fried sushi (deep fried anything, really)

Sex with fat people

Dessert at breakfast

Porn (kind of generic, yes, but best to keep it safe as people tend to get specific on this one)

Making porn

Chocolate

Listening to Oasis

Admittedly, most guilty pleasures, according to Western Aristotelian/Freudian ideas of "guilt," have to do with the basic drives: Food, Sex, and the occasional oddity showing up to validate Chaos Theory. But hearing all these stock responses pop up again and again made me wonder what exactly it takes to activate the reptilian brain.

Then I moved to Japan.

The rest was easy.

Call it the summer of 2005. I had been living in Fukuoka for over a year and was feeling the sort of inward glow of a white man on safari, but in a good way. I was speaking the language with some fluency, dabbling in the arts, and only dating one woman (not one of my students), a girl of natural beauty and, not being from the city, old-fashioned virtuosity.

It being a run-of-the-mill summer in Japan - humid and full of cicada din, fireworks, and little responsibility for the local non-Japanese community - of course, I drank regularly with several gentlemen from London who were interested in changing all that I had going for me, specifically the one girl part.

It was they who introduced me to the supposedly sanitized underworld of the Paid Clinical Trial Volunteer. They, the "Sick Crew" as I had dubbed them (we went boating a lot), kept mentioning large cash payments, few questions and, repeatedly, Russian girls. That was the clincher for them - Russian girls - who of course had little understanding of the English language, low morals and standards, and would be plentiful in the southernmost prefecture of Kagoshima where the trial was to be held.

As the beers flowed from the tap during that long, hot July night and we concocted our stories to get out of a week of work - paid, of course - I went along with the bulging eyes and exaggerated fish tales, along with the visions of crystal blue-eyed Muscovite princesses on holiday at their Japanese dachas, welcoming us international rabble with open arms and feeding us fresh Beluga caviar and ice cold vodka from sensuous matryoshka dolls until we were sated. At the end of the night, a pact was made. Sputum was expectorated. Blood was shook on.

In reality, in Japan at least, the paid medical trial volunteer gig is a lucrative and widespread phenomenon that is eerily clean and bereft of the toothless guy you meet coming out of the bar at 4am yelling "Massaaji, massaaji... Cheap!" or any other devious intention, at least so far as I knew. Imagine any part of legitimate Japan that interacts with the body: visits to the doctor's office, acupuncture, reflexology, facials, manicures and pedicures, the shiatsu massage and haircut combination.

Choose any one of them and visualize the sterile detail. Everything is painstakingly clean and sanitized. The practitioner is soft-spoken and well-versed. You are guided with polite smiles and well-placed cues toward a sense of extreme security and relaxation. There is a strong feeling of otherworldliness present. You can allow your worries to drop away as you are guided toward the floating world and the pure land via the true word.

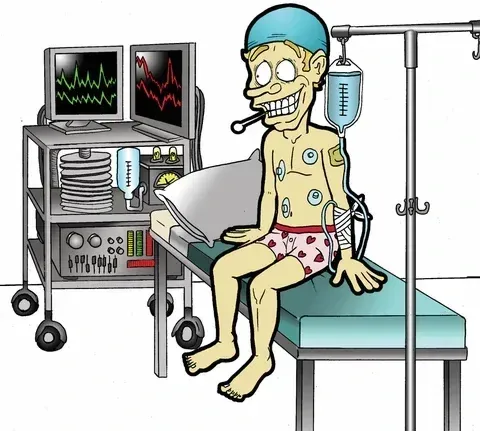

All hyperbole - and Russian girls - aside, it was that week that I found my guilty pleasure: I love to be poked and prodded, attached EKG suction cups to, tickled with stethoscopes, weedled and needled for blood, more blood, more and more blood, urine, stool, hair, mucus, saliva, nail clippings, x-rays, and awarded with motherly grins, cold hands, candy stripers, sponge baths, warm hands, Chupa Chups, happy face stickers, three-a-day bento meals, cat-napping, clinic-issued sweatsuits, doctor-led seminars on pharmaceutical trials, vending machines, Bikkle, and of course the equivalent in Japanese Yen of $3,000.

Arranging paid leave for the death of my beloved, though imaginary, brother Miguel had been easier than previously thought. What has been difficult since then is getting out of that world.

It's a syndicate.

It's a cycle with its own regulars who roam from north to south regular as the seasons. You come to recognize familiar faces and slowly conversations emerge, though names never do. You are a part of something bigger than yourself. Syphilis testing in Sendai. Nausea in Nagoya. Tokyo Tuberculosis. You become a number on a roll sheet, a face on a card, an undergarmentless Caucasian with of BPM of 24 and Triglycerides in the Michael Jordan range.

The paid monetary incentive for volunteers of the clinical trial, with which the four of us, having had to pretend we had no idea of the others' identities during testing, drank our fill for the three-day weekend we had before trekking back to Fukuoka for work on Monday, made us - and the surrounding community (often in awe of the veracity with which we consumed the local favorite: imo shochu) - a little richer, but it was something bigger than temporary cash in hand which made me wiser than before.

It was a sense of community, of donation, of blindly giving oneself to science, as well as the reassuring realization that despite my body being of certain scientific and therefore monetary value, I am special in a way that cannot be forced from me, but merely whooshed away by softly-spoken, foot-massaging, gently-caressing female Japanese medical workers of a median age of 25-40 and a smile so pure and eyes so warm, the angels speak reverently.

This article was originally posted in the August 2009 edition of JAPANZINE

Artwork by Adam Pasion

Nagoya Buzz

Events, local info, and humor for the international community of Nagoya, Japan.

Follow Nagoya Buzz :

Leave a Comment