At the time, my uncle owned the liquor store, and I delivered bottles for him on Mondays. I then went back on Fridays and picked up the empties. In this way, I got to know the whole town. Pretty much everyone did business with my uncle at one point or another.

Even though I was only twelve, he let me drive his delivery truck. The hills in town were too steep for a bike; plus, I had to carry around all those bottles.

Mr. Oi lived behind the temple and was so brown and wrinkled that he looked like a piece of fruit. You could barely make out his eyes. We kids called him Sumomo-san, Mr. Prune, though I was never sure if it was because of his appearance or his diet. He ate his dinner with the cats that lived near the temple. He just sat right on the ground. And he always ordered the same thing: twelve bottles of beer, two bottles of sweet sake, and a jug of shochu. All gone by Friday.

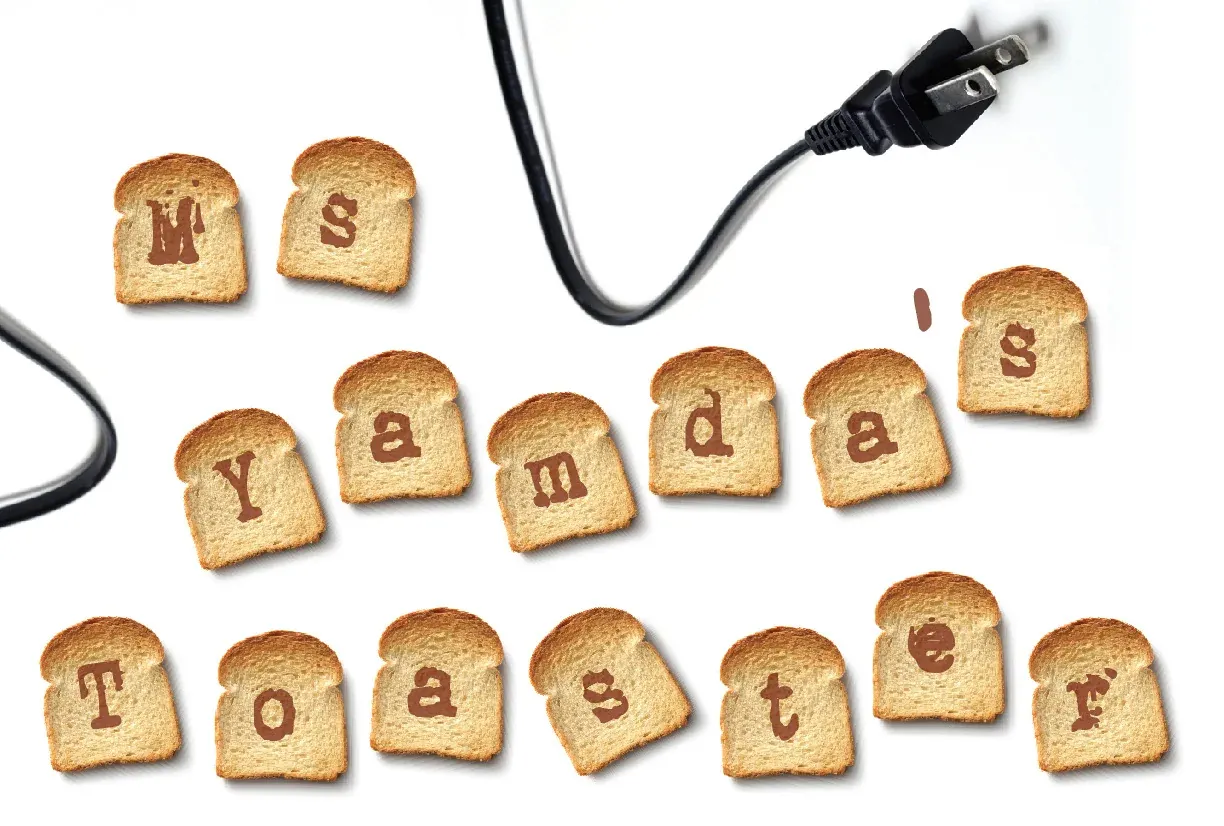

It was from Mr. Oi that I first heard about Ms. Yamada's toaster and how it could predict the way a person is going to die. I was setting the bottles on his mossy concrete doorstep when he appeared in the doorway and said in a voice as wrinkled as his face, "Son, today I learned how I'm going to die."

I had finished with the bottles and stood there, unsure what to say. I looked up at him because even though it's rude to look your elders right in the eye like that, it seemed to be what he wanted.

He smiled at me. "I'm going to die in my sleep. Can you believe it? Peacefully. I've been worried all my life about it, and now I know. Now I can live in peace."

I asked, as politely as possible, how he knew. He told me that Ms. Yamada had a toaster that when you put in a piece of bread, it came out with a character toasted on it. That character indicated how you'd die.

"So, sir, what was your word?"

"Sleep." He smiled at me, then waved as he shuffled back inside, a bottle of sake clutched between two hands.

I didn't tell anyone in my family what Mr. Oi had said. My parents were too busy — that was the year they opened the udon restaurant — and my sister had just got a boyfriend and never hung around after school anymore.

Plus I had a feeling no one would care. I was raised in a family of skeptics. We didn't observe any superstitious holidays, bean-throwing day, or Tanabata, or anything like that; all we celebrated was New Year's, and that's because you get to feast for three days straight.

I picked up Mr. Oi's empties on Friday and brought him an extra two bottles of sake which he'd special ordered that week. On Monday, he was dead. Died in his sleep, just as he'd said.

Apparently, Mr. Oi had told a lot of people about Ms. Yamada's toaster and its prediction for him, though, because once he died, everyone in town was talking about it. I guess no one had thought anything of it until then.

Ms. Yamada had always been a little weird. She confirmed everything: the toaster had predicted her husband's death last year when it popped out a piece that read "heart" three days before he had a coronary, and after that, it had foretold her mother-in-law's fatal pneumonia.

She wasn't sure of it until now, but that toaster definitely had powers. A gift from God, she told the crowd gathered around her at the market, smiling, holding the toaster under one arm, its plug swinging beneath it like a tail.

When asked if she'd gotten a death-predicting piece of toast herself, she said she had.

"Well?"

Hers had read "Cancer." It was quiet for a while after that.

Like I said, Ms. Yamada was just like any other lady you'd see around town except for one thing—she was a real religious nut. Years before the toaster, she'd knocked on our door a couple times, offering her "help." I remember thinking it was kind of nice — weird, but nice — but after she'd gone, my mom would roll her eyes and go back to her TV drama. Anyway, that was back when I was little. By the time the toaster came around, Ms. Yamada didn't knock in our neighborhood anymore.

Her house was at the edge of town, partway up a huge, terraced hill with bamboo at the top. I drove over there every week. For a widow living alone, she had a pretty big standing order at my uncle's store — eight tall one-liter bottles of beer. I always wondered what she did with it. That was more than a liter a day! She who smelled so sweet it hurt your nose, like overripe peaches, and spoke very properly and always wore something with lace on the collar; how could she go through that much beer?

I thought of her at her impeccable kitchen table, pouring the beer into a glass and waiting patiently for it to settle, then taking the tiniest sip. I pictured her melting at the first drop of bitter liquid in her throat, her creamy makeup running down her neck, and the starch on her collar drooping until her whole body oozed into a peach-scented puddle of foam.

The toaster became a sensation. Some people thought it was a trick she was using to try and convert people, while others believed in the toaster but disagreed about what ought to be done with it. Some wanted to put it in a shrine and worship it like a Shinto deity. Others thought she should sell it to the government.

But the thing people argued about most was whether or not it was right to use the toaster's powers to become One Who Knew. Soon, the town divided itself between Knows and Didn't-Want-To-Knows. Each group, of course, claimed the moral high ground — there was no room for compromise. Conflicting opinions on the topic spoiled countless friendships and were even named in the Satos' divorce proceedings as evidence of irreconcilable differences.

Ms. Yamada didn't get involved in the politics of it. She let anyone use the toaster. She believed it was a gift from God that should not go to waste. Every day, there was a line out her door of people hoping to find out in what fashion they would meet Death.

But some of the Didn't-Want-To-Knows were upset. One man, a retired professor from Keio University, who everyone just called "Mr. Doc," went so far as to stand at Ms. Yamada's open door and protest. He was there talking quietly and intently to a young mother and her toddler on the front steps when I came the next Friday to drop off Ms. Yamada's beer. They paid no attention to me as I stepped past and set the bottles in the entranceway. I could hear someone crying in the kitchen.

On the way out, I passed the mother and child, who were walking toward the road with Mr. Doc. I guess he'd convinced her not to go in. I kept my head down, but as I passed, he called to me.

"Keisuke."

I turned, stunned he knew my name.

"Are you planning to find out?"

I shrugged, then shook my head. It seemed like an awful big thing to know. Plus, I kind of liked thinking that maybe I'd never die, like by the time I got old they'd have invented a cure for everything.

"I'm fighting a losing battle," he said. "You just can't protect people from themselves."

I nodded, then bowed slightly and walked quickly back to the truck. On the drive down I passed four groups of people climbing the hill to Ms. Yamada's house. I wondered if Mr. Doc would be able to stop all of them.

By Monday, every house I visited was buzzing with talk of the toaster. Mrs. Kawabata was predicted to die by fire—the same as Mrs. Shinjo. Both were librarians, so they decided that there would be a fire at the library. Extra fire extinguishers were purchased for the older wooden building, and a new state-of-the-art sprinkler system was installed.

A newlywed couple canceled their honeymoon flight to Hawaii because both of their pieces of toast had popped up bearing the character "air."

At dinnertime, my parents and sister talked about how nuts everyone was, but I kept quiet. I didn't necessarily believe in the toaster, but at least I was willing to believe... maybe.

Over the weekend, the news seemed to have reached all over the prefecture. The line spilled out Ms. Yamada's door and down the steps. News vans crowded the narrow street so that I had to drive fifty meters away to find room to park.

Mr. Doc held forth on the front stoop. "Don't let curiosity pollute your mind!" he bellowed at the line, which was full of unfamiliar faces. A few college-age kids stood with him, holding signs and chanting, "Knowledge of death sullies the will to live!" The crowd ignored them and was silent, as if in line to receive a blessing.

I stepped through the mob with the beer, excusing myself and sneaking peeks at the faces. Some people seemed lost in thought, staring up at the bamboo grove beyond the house, while others whispered nervously to one another.

"Hey, no cuts, buddy," someone said as I passed. I held up the crate of beer and almost said, Delivery, but then I thought that maybe Ms. Yamada didn't want these people to know she'd ordered all this beer, so I turned back.

I lingered near my truck and watched people come down the stairs, each clutching a piece of toast. So many People Who Knew. Some looked confused, and some relieved. One woman was bawling so hard she dropped her toast, and when she did, I saw what it said:

"Suicide."

That was eerie, but even eerier were the ones whose faces were blank and empty and lost. Like maybe they were already dead.

A cry rose from the front of the crowd, and suddenly, everyone got very noisy. Something exciting had happened. People gestured and talked amongst themselves, and some turned away and started heading back toward the road.

"Broken? Right! I knew it had to be a fraud."

"Just my bad luck… should've come earlier."

"Not really sure I wanted to know, to be honest…"

The toaster had stopped working? I waited until everyone left, then approached the door with my crate.

"Ms. Yamada?"

She stepped into the hall, prim as ever.

"Keisuke! How good of you to come amid that throng. I noticed the truck outside earlier and thought you'd given up."

"No, ma'am." I held the bottle out to her, and she took it without saying a word. I shifted around, trying to sneak a peek into the kitchen.

"Come on in and have a drink," she said, motioning me into the kitchen with a warm smile.

There it was, unplugged, sitting right smack in the middle of the round yellow table; a silver singe-slice toaster trimmed in black with rust lining the opening. The table was littered with crumbs. I wondered if you had to eat the toast in order for the prediction to come true or if just toasting it was enough.

I tried not to stare.

She gestured at the table. "Well, there it is."

"Is it…broken?" I asked.

"Seems to be." She frowned.

"Did it really work, though"?

Her smile returned, serene beneath her lace collar. "Oh, yes! God's methods sure are beyond our comprehension. Who are we to judge His ways?"

"But…maybe we... you... can get it fixed?"

"Mm, maybe. But perhaps this is simply the appliance's fate."

She took a bottle from the crate and gestured with it toward the back door. "Please, come."

I followed her out the back door. The yard had been completely overtaken by a jungle-like garden that seemed out of step with Ms. Yamada's tidy appearance and manners. We picked through vines until we reached the back of the yard, where a stone shrine stood against the first tall mud terrace.

The family grave.

This is where my ancestors rest, and most recently my husband, she said, picking up the bottle opener lying at the base of the shrine.

"He loved beer. His favorite thing in life was a cold beer in the garden at sunset. Ah, Shuji", she said.

She opened the beer deftly and poured it all over the shrine, slowly dousing the statuary in caramel foam. She shook the bottle wildly at the end, spraying us both with drops of beer. She looked like my sister dancing to a Morning Musume song when she did that.

When the bottle was dry she set it on the ledge where offerings are left. The family name, Yamada — "heavenly mountain and earthly rice field" — was carved in fancy calligraphy above the shelf, and beer meandered down the grooves in the stone like a lazy river in summer.

She sighed. "I do that every day. That is my offering to him."

After what I'd just witnessed, I felt comfortable enough to ask Ms. Yamada, what about the eighth bottle?

She laughed. "You are an astute fellow."

She went into the house and returned with the toaster and another bottle.

"Do you know what baptism is? "

I shook my head.

"Baptism is a ritual that washes away original sin," she said, setting the toaster on the offering ledge. She reached again for the opener. "It makes you pure."

Then she held the bottle over her head, closed her eyes, and turned it upside-down.

I reached out automatically to help her, to save her from herself, but she raised her palm. The beer gushed over her hair, her face, onto her white starched shirt and long beige skirt. Her hair flattened out. Here and there, her cheek makeup ran and revealed darker skin underneath.

About three-quarters through, she stopped, opened her eyes, and held the bottle out to me.

I didn't move. All I could hear was the drip-drip-drip of beer hitting the dirt around Ms. Yamada's feet. I know what my uncle would've said: what a waste of alcohol. He always said it was a sin to waste liquor.

My impulse was to take the bottle — maybe she wanted me to hold it for her — but then she raised it to the sky and said, For once, they came to me. I did the best I could, I explained what God truly is and how to be saved, but no one listened.

The remaining beer sloshed around inside the bottle. Her eyes were closed. It seemed she'd forgotten I was standing there.

They just wanted the piece of information, she said. Like I was some kind of palm reader! When the show was over, they left as quickly as they had come.

She opened her eyes and looked around, teetering as if she'd drunk all that beer instead of showering in it. When she noticed I was still there, she held the bottle out to me once again.

Strands of wet hair clung to her cheeks. She smiled, a smile I've never forgotten, a smile like a girl playing in a puddle.

I stepped close to her, close enough so that I could see the pink brassiere through her damp blouse. Together, we emptied the bottle into the toaster's two vacant slots. When the slots overflowed, she pushed down the lever on the side.

She looked toward the sky. I wondered if she was thinking of her own death. I guess I know how she's going to go, I thought.

I followed her gaze. I could see the hilltop behind us and the bamboo growing there. The stalks moved slightly in a breeze I couldn't feel, revealing and concealing slivers of blue that formed words faster than I could read them, a marvel for anyone who cared to look.

By Kelly Luce

Originally published in the November, 2008 issue of Japanzine

"After subscribing to the weekly Nagoya Buzz newsletter, I was suddenly able to see the future!"

"Every train delay announcement in 2026 will be delivered by interpretive dance!"

- Bob from Imaike

Nagoya Buzz

Events, local info, and humor for the international community of Nagoya, Japan.

Follow Nagoya Buzz :

Leave a Comment